The surprising ways that Victorians flirted

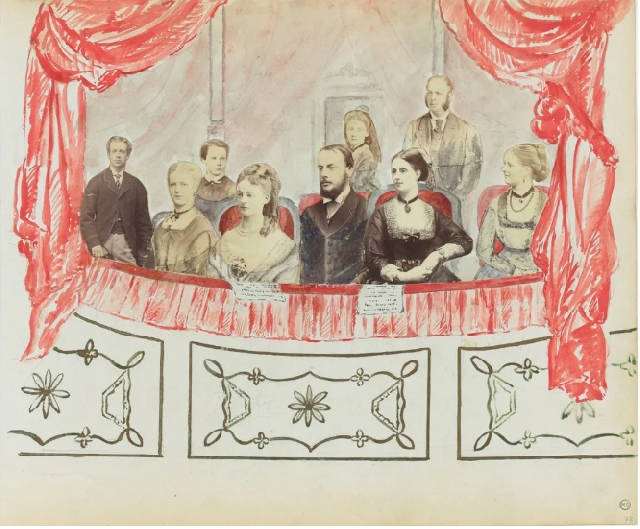

Cartes de visite albums were ways to see and be seen, like going to the theatre, as shown in this image (1866-1871) by Georgiana Louisa Berkeley (Credit: Musée d'Orsay)

Cartes de visite albums were ways to see and be seen, like going to the theatre, as shown in this image (1866-1871) by Georgiana Louisa Berkeley (Credit: Musée d'Orsay)

Look up the term "collage", and the Tate's website will inform you that this cut-and-paste method for making new work was "first used as an artists' technique in the early 20th Century." Generally, Picasso and Braque get credited with inventing collage, with Picasso's decision to paste oilcloth into his painting Still Life with Chair Caning in 1912 considered a firing shot for an explosion of avant-garde art. And when photographs were included in such mixed-media works, the results were particularly witty, subversive, or downright unsettling – as seen in the photomontages by Dadaist Hannah Hoch and Surrealist Max Ernst, revolutionary Soviet artists Alexander Rodchenko and Varvara Stepanova, British pop artists like Richard Hamilton and Peter Blake, and Linder Sterling's punk collages.

So far, so coherent a journey through 20th-Century art trends. But what if the Cubists, the Dadaists and the Surrealists were actually predated in this innovation by… upper-class Victorian society women?

Around 1860, Britain was gripped with a craze for cartes de visite – small photographic visiting cards, featuring staged portraits of the owner. It became de rigueur to swap cards, with even only vague acquaintances eagerly collecting each other's image for their scrapbooks. Making photocollages in dedicated albums – by cutting up those calling cards and repurposing them within watercolour painted backdrops, to often silly, surreal or even suggestive effect – became quite the fashionable activity for members of the British aristocracy. Admiring each other's albums in drawing rooms was a popular after-dinner pastime.

In recent decades, the art of Victorian photocollage has become of increasing interest to photography and art history scholars – a book, Playing with Pictures by Elizabeth Siegel, was published in 2009 alongside an exhibition curated by Siegel at the Art Institute of Chicago, which then toured to New York's Met Museum. Yet no dedicated exhibition has ever been hosted in the UK. Many of these albums still lurk in British country homes, undocumented by art historians, and this fascinating trend remains little-known to the general public.

There are many reasons for that, not least the fact that the people – mostly, but not exclusively, women – who made photocollages were doing so as a source of entertainment for their own social set, rather than creating artworks for display in a gallery. Photo collaging was considered an accomplishment, rather than a fine art.

"A degree of ability to draw or watercolour paint, do ink work or cut paper work, were things that young women from the upper middle classes were taught," says Patrizia Di Bello, Professor of history and theory of photography at Birkbeck, University of London. "But there wasn't anywhere else to take these skills." Like drawing and painting, photo collaging could only ever remain a hobby for these women, although the amount of time and effort some albums display suggest they did offer a considerable creative outlet.

Nonetheless, being considered "accomplished" was also important in its own right, as a social rather than artistic skill: it meant you were a good guest or host. Di Bello points out that, after Queen Victoria did away with balls and dancing at court (wanting to project an image of gravity and respectability), "young women who had albums – whether watercolour or photographs – were prized because they gave the court things to do. It did give you a social currency."

Cut-out heads are spliced onto the bodies of ducks or monkeys, juggled by jesters, or smoked out of a pipeWhile there are no good sources detailing what people thought about specific photocollage albums, their function as a shareable entertainment is surely what led to some being so, well, inventive. Many offer little more than pretty embellishment of photographs – but some others prove witty, surprising, and mischievous.

Cut-out photographic figures are placed within painted drawing rooms or landscapes, but also more imaginatively arranged as if performing circus tricks or lost at sea, caught within a bird's nest or spider's web, or stuffed into pickle jars to be speared out with a fork. Cut-out heads are spliced onto the bodies of ducks or monkeys, juggled by jesters, or smoked out of a pipe. They're delightful, and they're often weird.

"Albums which are decorated in some way are fairly common," says Dr Marta Weiss, senior curator of photography at the V&A. "But it's much more unusual to find ones that have this more imaginative, wacky, surrealist type collage."

The most ingenious were surely designed to dazzle the viewer with the maker's creativity, or their humour. Many contain visual puns, or in-jokes and coded messages, strengthening our understanding of these albums' social function – something for men and women to chuckle over together. They were even, Di Bello suggest, a means of flirting – both via what's depicted on the page, and simply through providing men and women with an excuse for sitting close together, to flick through an album.

Insta-collage

Photography itself was still a young art when these albums became fashionable – and it was the rise of affordable, mass-producible photographs that led to this playful approach to collecting and display. "The albums were understood as the social media of its time," says Di Bello; collections of cards a sign of status much like Facebook or Instagram friend requests and follower counts.

But you could also purchase cartes de visite of famous figures, including the Royal Family; inclusion in an album could be a sign you were personally acquainted, or just that you'd paid for their picture, adding an enjoyable level of gossipy intrigue.

As photography becomes more and more produced on an industrial level and available to all, this is a way to de-democratise it – Dr Marta WeissAnother result of this was that merely displaying your cartes de visite was soon no longer good enough – and photo collaging became a way to elevate these mass-produced items that even the general public could simply buy in a shop into something rather more special. Only ladies of leisure would have the spare time, the watercolour skills, and the resources to craft such albums – cartes de visite might be fairly affordable, but to chop them up as an amusement would have still seemed lavish to all but the most well-off.

"As photography becomes more and more produced on an industrial level and available to all, this is a way to de-democratise it," explains Weiss. "They're taking something mass produced and then customising it, but it's also taking something machine produced and adding hand work to it."

Photocollages were certainly a means for their owners to flash their social status, accomplishment, wit, and society connections – not only by literally who they had photos of, but also how bold they felt able to be in playing with that person's image. And some are pretty bold, flirtatious and suggestive, upending received notions of Victorian propriety, Di Bello suggests.

One of her favourite examples is within an album by Lady Filmer, wife of MP Sir Edmund Filmer. It initially looks all very respectable: a drawing room scene featuring Lady Filmer with her own photocollage album (the collages are very frequently self-referential like this; Frances Elizabeth Bree's even features a miniature pop-up album, where you can turn the pages). The Prince of Wales is in attendance, but so are Lady Filmer's husband and brother, while her sisters' cut-out faces are turned into watching portraits on the walls.

But the Prince of Wales was a known philanderer, and he and Lady Filmer had struck up a rather suggestive correspondence, constantly sending each other photographs (astonishingly, via letters sent between the Prince and Sir Filmer himself – the audacity!)

"The Prince of Wales was courting Lady Filmer by sending photos of himself almost daily," says Di Bello. "And we discovered that one of her daughters was known as Queenie in the family – rumoured to in fact to be the daughter of the Prince of Wales..."

Knowledge of such salacious gossip inevitably changes the meaning of the image. Suddenly, it's very noticeable that Lady Filmer is posed looking at the Prince, while her husband remains oblivious.

But nor is the image explicit enough to cause any problems. "If I'm somebody who's an acquaintance, then I'm just impressed that the Prince of Wales is part of her circle," say Di Bello. "But if I'm in the know, I can take more gossipy pleasure – or even jealousy – about her flaunting her connection."

Di Bello also points to the implications of a photocollage of the pickle jar full of people. We may not know the exact relationships between them, but Di Bello suggests that the label on the bottle – "Mixed Pickles" – and the way the men and women are jumbled up together implies that "these people had got themselves into a pickle!"

Photo collaging may have provided a fairly safe way for women to flirt – it's a slow and painstaking craftA degree of skill at flirting seems to have been admired in the Victorian era, Di Bello discovered from research into etiquette books, books of parlour games, and Victorian fiction. "Some flirting was part of what made a social occasion fun, but it wasn't supposed to go any further. It was always meant to [have] a very clear boundary. But in some circles, perhaps it was understood that these boundaries could be broken… So the idea of the guest guessing if things [depicted in photocollages] are really happening or not was part of the fun!"

Photo collaging may have provided a fairly safe way for women to flirt – it's a slow and painstaking craft; there can be no unfortunate slip of the tongue or accidental moment of indiscretion. Women – always the ones who bore the cost of going too far in a flirtation – had a degree of control and agency when it came to adding just-the-right-amount of intrigue to their collages.

Some can be surprisingly explicit, however. Another by Lady Filmer shows a fox-hunting scene: she is the fox, while the pack of dogs hunting her all have men's heads. Her husband is on foot, rather than horseback, desperately trying to control the dogs…

"It seems almost openly feminist," say Di Bello. "On the one hand, she's showing off that men come to pursue her – but if they catch her, she's going to be devoured. It's playful, then you realise 'oh my god, this is actually quite disturbing'. She's clever, but she's taking a big risk."

Men did make photocollages too. But it seems that their albums were more often dedicated to documenting what they did or were interested in, rather than purely a social milieu. "Men's albums related to their public identity: sites they've visited, travels they'd been on, bridges they had worked on – those kinds of things," says Di Bello. The album belonging to venture capitalist Sir Edward Blount, for instance, includes cartes de visite showing men in military and business attire, or landscape shots showing colonial trade ports, as well as masculine leisure pursuits such as horse-racing and shooting. This suggests the album was a means of self-promotion for him, for impressing potential clients entertained at home.

Weiss adds that photocollages need also to be seen within the context of wider cultural trends – some of the prettier ones illustrate popular fairy tales, or take inspiration from John Tenniel's fantastical illustrations of Alice in Wonderland. But Tenniel also worked as a caricaturist for the satirical magazine Punch – and there is a degree of overlap between caricatures and photocollage, especially in men's albums. "I've seen examples of playful photocollage work that was made in the context of an all-male social club – heads put onto painted bodies in a caricature kind of way," says Weiss.

At first glance, Victorian photographs and watercolour scenes may look distinctly quaint to modern eyes. But look closer, and their cheeky juxtapositions and sly humour can help puncture our overly narrow notions of Victorian high society.

While they may not quite have the revolutionary fervour or subversiveness of avant-garde 20th-Century artists, these Victorian creators nonetheless were taking the latest technology of their time and playing with it in wholly inventive new ways – to flirt, to show off, to strengthen social ties, but also to delight, to amuse, perhaps even to shock or unnerve. In its own way, this drawing-room art really was cutting edge.

Source: BBC

Trending Features

Did God choose you? Rethinking love, marriage and the choices we make

15:20

Nii Ayikoi Otoo: Lawyer, statesman and leading voice for Ga-Dangme advocacy

20:07

‘It is not as long as you think’

19:20

“When grief met purpose: Andrews Kwame Perprem’s defiant stand for Ghana’s forgotten mining communities”

09:26