“We must exercise our independence”: Djokoto’s bold case for marijuana legalisation

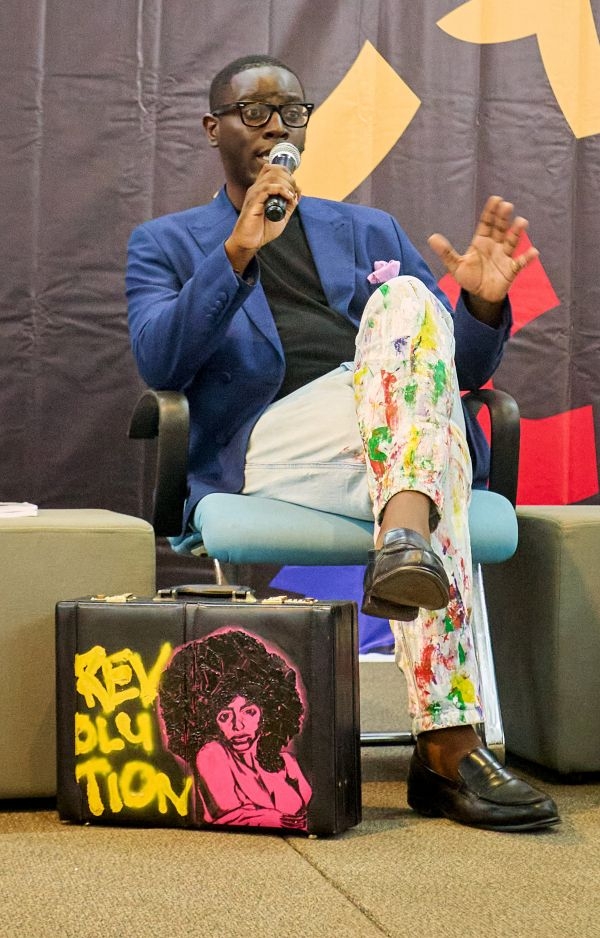

Vincent L. K. Djokoto

Vincent L. K. Djokoto

In a wide-ranging interview on Class 91.3 FM on Thursday morning, recorded at the Ka xoxowo Salon — V. L. K. Djokoto’s live-in art gallery — cultural theorist and financier Djokoto made an impassioned yet meticulously argued case for marijuana legalisation in Ghana, framing the issue as one of economic sovereignty, social justice, and what he termed “honest cultural conversation.”

Djokoto, who leads the historic D. K. T. Djokoto & Co. multi-family office and has emerged as one of Ghana’s most cerebral voices on Pan-African cultural and economic policy, spent nearly 45 minutes outlining legal, economic, and cultural arguments for reform — challenging what he described as “colonial-era prohibitions that serve neither our youth, our farmers, nor our national interest.”

“An Artifact of Imperial Control”

The 30-year-old gallerist and author began by addressing the legal foundations of Ghana’s current cannabis laws, tracing them to British colonial imposition.

“We must be clear-eyed about the origins of prohibition,” Djokoto told host Zita Okwang. “These laws were not crafted by Ghanaians, for Ghanaians, with Ghanaian interests at heart. They were instruments of colonial control, imposed without consultation with our communities.”

He continued: “That we maintain these laws intact, nearly seventy years after independence, represents what I would call an extraordinary gap in our decolonisation project. We achieved independence in 1957 — we must now exercise that independence fully and keep its spirit alive. We have decolonised our politics, our education system — to varying degrees — but our drug policy remains frozen in the colonial imagination.”

Djokoto pointed to the human cost of current enforcement, noting that thousands of young Ghanaians, predominantly from rural and economically disadvantaged backgrounds, face unconscionably harsh prison sentences for cultivating or possessing cannabis.

“These are not dangerous criminals. These are farmers, students, young people making choices that harm no one,” he said. “Yet we imprison them — often for years — destroying their futures, fragmenting their families, perpetuating cycles of poverty — whilst our police forces and courts dedicate scarce resources to prosecution rather than addressing violent crime, corruption, the things that genuinely threaten our social fabric.”

When pressed on whether legalization might increase youth access, Djokoto was characteristically measured but firm.

“Prohibition has demonstrably failed to protect young people,” he responded. “In our current system, illegal dealers check no identification, respect no boundaries, provide no quality assurance. A regulated market with licensed retailers, robust enforcement, and substantial penalties for sales to minors would provide immeasurably greater protection than our current approach.”

“Billions in Lost GDP, Millions in Uncollected Revenue”

The financier’s most striking arguments centered on economic opportunity, an area where his expertise in multi-generational wealth management and rural banking brought particular authority.

“Ghana’s economic potential in legal cannabis is, quite frankly, staggering,” Djokoto argued. “Our climate, our agricultural expertise, our strategic position in West Africa — we are positioned to become the continental leader in what analysts project will be amongst the world’s largest and fastest-growing industries over the coming decades.”

He offered a stark comparison: “Current prohibition forces this value creation underground or abroad. Ghanaian farmers who could be supplying legal medicinal markets across Europe, North America, throughout Africa — these farmers instead risk imprisonment while foreign corporations in Canada, the Netherlands, increasingly throughout the continent capture market share that should rightfully be ours.”

Djokoto cited Colorado’s experience, noting that the American state — with a population smaller than Greater Accra — generates over $400 million annually in cannabis tax revenue.

“Ghana could realistically generate similar revenues within five years of legalization,” he said. “We are talking about fifty to one hundred thousand direct jobs, billions in GDP contribution, revenues that could fund education, healthcare, rural infrastructure — revenues currently enriching criminal networks rather than our national treasury.”

The cultural theorist emphasized that a legal cannabis industry would create multiplier effects across Ghana’s economy: agro-processing, pharmaceutical development, packaging, transportation, financial services, quality assurance.

“This is not merely about marijuana,” Djokoto explained. “This is about building integrated value chains, about formal-sector employment for our youth, about sustainable income streams for rural farmers who currently struggle with volatile cocoa and cashew prices.”

“We Must Speak Honestly About Cultural Reality”

Perhaps most provocatively, Djokoto challenged what he characterized as Ghana’s “cultural dishonesty” around cannabis consumption.

“Marijuana use is already widespread across Ghana,” he said simply. “University students, professionals, artists, farmers — consumption crosses every demographic boundary. We all know this. Prohibition has not stopped this reality; it has merely ensured that consumption happens without quality control, age verification, or tax contribution.”

He acknowledged concerns about social harm but argued that these concerns actually strengthen the case for legalization.

“I understand the moral discomfort some Ghanaians feel,” Djokoto said. “But we must ask ourselves: does prohibition actually advance our moral objectives? Does it protect our communities? Or does it simply criminalize choices while generating zero public benefit?”

The author of ‘Revolution’ also touched on cannabis’s role in Ghanaian spiritual and cultural practices, particularly among Rastafarian communities and within certain traditional healing contexts.

“Prohibition has criminalized these practices, forced them into shadows — even as we simultaneously celebrate our cultural diversity, our religious freedom, our indigenous knowledge systems,” he noted. “There is a contradiction here that we must confront.”

Djokoto pointed to the global shift in cannabis policy, mentioning Canada, Uruguay, Thailand, Germany, and portions of the United States as examples of nations that have embraced legalization.

“These are not reckless societies,” he said. “These are nations we admire, nations we trade with, nations with robust public health systems. They have concluded, based on evidence, that prohibition causes more social harm than the substance itself. Are we to believe that Ghanaian policymakers and public health experts are less capable of managing legalization than their counterparts in Ottawa or Bangkok?”

“Ghanaian Solutions for Ghanaian Realities”

When asked to outline a practical path forward, Djokoto proposed what he described as a “uniquely Ghanaian framework” for legalization.

“This need not mean American-style commercialization without limits,” he clarified. “We can design an approach that prioritizes small-scale farmers over multinational corporations, emphasizes medicinal applications alongside regulated recreational use, channels tax revenues toward education and rural development.”

He suggested establishing a Marijuana Regulatory Authority modeled on Ghana’s Food and Drugs Authority, with responsibility for licensing producers, enforcing quality standards, restricting advertising, and funding public health education.

“I would advocate for a phased approach,” Djokoto said. “Begin with full medical legalization and decriminalization of possession. Establish robust regulatory infrastructure. Then transition to regulated adult-use sales, with licensing preferences for Ghanaian citizens — particularly those from communities most harmed by prohibition — and for smallholder farmers rather than industrial-scale operations.”

Revenue, he argued, should fund drug treatment programs, mental health services, youth education initiatives, and agricultural extension services for farmers transitioning from informal to formal markets.

“We must ensure that the benefits of legalization flow primarily to Ghanaian communities, not foreign investors,” he emphasized.

“Leadership Requires Courage”

In closing remarks that echoed his Pan-Africanist philosophy, Djokoto framed cannabis legalization as an opportunity for Ghanaian leadership on the continent.

“Ghana has led Africa before,” he said. “First to independence, pioneers of Pan-Africanism, leaders in democratic governance. We can lead again by demonstrating that cannabis legalization — implemented thoughtfully, with strong Ghanaian institutions and values at its center — represents economic wisdom, social justice, and cultural honesty.”

He added: “The question is not whether Ghana will eventually legalize cannabis. Global trends and economic realities make this inevitable. The question is whether we will lead this transition, capturing its benefits for Ghanaian farmers, entrepreneurs, and citizens — or whether we will lag behind while other nations build the industries and expertise that should be ours.”

When host Zita Okwang suggested that such proposals might face significant political resistance, Djokoto was philosophical.

“Every transformative policy initially faces resistance from those comfortable with the status quo,” he acknowledged. “But leadership means recognizing when inherited laws no longer serve our people’s interests and having the courage to forge new paths. Our youth deserve better than criminalization. Our farmers deserve opportunity. Our nation deserves policies grounded in evidence and justice rather than colonial-era moral panic.”

He concluded: “Ghana cannot afford to remain spectators in a global economic transformation. The time for this conversation — and for action — is now. We need only the courage to act.”

Source: Classfmonline.com/Zita Okwang

Trending News

W/R: 2 arrested over viral assault video involving teenagers at Effiakuma

20:02

Mahama unveils initiatives to boost healthcare, food security and education

13:49

Empowering Ghana’s future: Japan’s scholarship programme drives a new era of Ghana-Japan co-creation and leadership development

18:50

Age should not define Leadership – John Alexander Ackon backs Dr. Frank Amoakohene’s performance in Ashanti Region

11:11

O/R: Police seizes cannabis worth over GHS1.4m from impounded truck

19:31

Teachers and parents demand sacking of Anloga District Education Director over alleged mismanagement

18:20

Kojo Oppong Nkrumah slams gov't's 24-Hour Economy law as 'PR stunt,' says it lacks legal muscle

12:24

Energy Ministry reaffirms commitment to rural electrification and grid stability

09:58

A/R: 4 arrested over robbery attack on okada rider at Fomena

19:57

December 19, 2022 marked one of the darkest days in Ghana’s economic history

12:23